Houndstooth - a many-faceted investigation as to its origins, history, nomenclature, definitions, newspaper reports, fashion, popular culture, popularity and underlying mathematics over nine dedicated web pages

Introduction Doubtless readers of this page will be familiar with what is known as the ‘houndstooth’ tessellation, seen extensively worldwide, as used on a multiplicity of garments and man-made objects. You name it and it’s there; coats, blazers, dresses and skirts and other outdoor wear, and also and indeed, on numerous other artefacts too; Chevrolet upholstered its Camaro, and novelties, such as pet dog bowls, to name but a few of the many other instances. Indeed, it’s so popular that no other tessellation can come anywhere near it in terms of frequency of usage (and so hence one of the many subtitles); any other tessellation used on garments and man-made objects pales in comparison. Typical of female fashion (although indeed also worn by men and was indeed originally the preserve of menswear and not women), it has remained popular since its beginnings in 1925 (or at least as first recorded) and indeed throughout the years to the present day, and of which has aroused my interest in this. Indeed, it has never seemingly gone out of fashion. Upon having seen this frequently in my everyday life on the streets of Grimsby, UK, in c. 2009 (or so as I recall), I then decided to investigate this more extensively in the course of my (wide-ranging) tessellation studies. In short, this is an investigation into its history, popularity, and later, with its underlying mathematics, and encompassing fashion and celebrity. A single page is simply not enough for such an extent. Broadly, for each distinct aspect, I create a dedicated page. This includes an introduction (here), origins, history, nomenclature, definitions, newspaper reports, fashion, popular culture, underlying mathematics and a miscellany, all in various states of development. Simply stated, of such a varied, wide-ranging study, there is so much material, especially from the 1970s onwards, that it is impractical to show ‘all’, even as an outline or concept. Indeed it is overwhelming! Therefore, this should be bone in mind when reading. Many other worthwhile instances are omitted arbitrarily. My main interest is in the historical aspects, arbitrarily defined as the 1960s and earlier (the earlier the better). This at least permits a modicum of thoroughness, although even here, even for the 1960s, 1950s and 1940s even, there is still an abundance of material to survey. Again, this is not claimed to be all-exhaustive but is at least of a more thorough nature than of the latter-day instances. An open question is as to how and why this pattern has come to the fore – what explains its undoubted position as the world’s most popular tessellation, in terms of usage on a whole variety of fabric material and objects, of which this study attempts to answer, amongst other concerns. As such, I consider that there is no simple answer! In itself, the tessellation is nothing special in terms of its aesthetics, there are other ‘simple’ instances, such as the Cairo tiling, which is far superior. As such, it seems to have gained a foothold in terms of use as a fabric, of which it is then used as the de facto pattern in that world, before expanding to the usage of other objects, from which it is was then used subsequently ubiquitously by default. As such, although the investigation is indeed thorough, this is very much a work still in progress. The full story is still to be told if it ever will be, given the various complexities. And indeed, at the age of 60, I may simply run out of time. Likely, as with other unrelated studies, the sheer extent will overwhelm me and I will become exasperated, and so put this aside for a while. I have previously returned to the topic intermittently, with previous studies of 2009, 2012 and 2015, and now late 2018-early 2019 which leaves the previous studies far behind in all aspects. Indeed, there is no comparison. The latest update, building on its predecessors, is a notable advance in depth, on all aspects. However, there is still much work to do! In particular, this refers to the mathematics, of which I haven't even started (or at least published; I have made minor studies previously). In the meantime, I thoroughly recommend the work of Douglas Blumeyer and Loe Feijs. Both stand head and shoulders above any other mathematical writings. See the page ‘Webpages of Interest’ for links to their work. As such, given the broad houndstooth spectrum, it is possible to spread oneself a little too thinly here, resulting in not a lot being firmly established or decided in any one topic. To try and avoid this, I have concentrated on the history aspect. Upon completion, or as much as I desire to undertake, I will move on to other matters, such as the mathematics. Suggestions and corrections are welcome. In contrast to previous updates separated by many years, when I do decide to put the study aside for a while upon the 2019 return, I intend to return to the study more frequently, as time permits. Below on this introductory page I discuss houndstooth in a generally broad sense, with the origins, and other generalised matters, with more specific aspects, notably the history, as a series of dedicated sub pages. I might just add that due to the constant research, then writing, over many months, and with new pages, page alterations, adding to text, revisions, this may not be entirely consistent, with occasional overlaps or indeed exemplary presented! However, although this may be so, it is still nonetheless a fine work of scholarship of its type. For sure, especially as to the history aspect, there is nothing better.

Beginnings - Origins as a Weave This essay thus examines background details, its beginning, and subsequent developments. However, note that there is very little original research on my part here (at least so far); all documentation that follows is taken from books, articles, and websites, with facts, especially from the latter largely taken on trust, and personal correspondence.

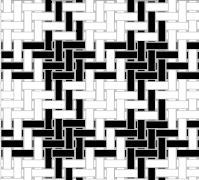

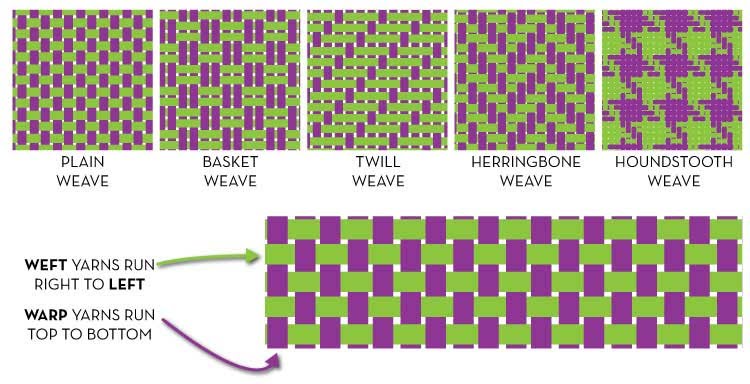

Origins The origins are decidedly obscure, and hazy, to say the least, with conflicting accounts! It seems almost de rigueur not to mention sources. First, one must be clear as to definitions; the term houndstooth is used so casually to describe a whole series of geometric black and white designs that almost anything goes! Further, as an aid in such matters, early (however so defined) pictures are lacking. Precision is needed, of which I will attempt to address here. In short, it would appear that the commonly accepted design began as weave (followed by, at an unclear date, the alternative straight-lined version, without the jaggedness of the weave). Technically, this is described as a 2/2 twill, two over/two under the warp, advancing one thread each pass, typically with black and white threads. Note that the weave is not shown as tessellation as such, but rather as a frieze. As such, the design appears to arise ‘naturally’ as a result of the basic weaving process, and so is thus common (in contrast to other jagged geometric designs of a tessellation nature). Basic Types of Weave It is generally stated that houndstooth originated in Scotland (of which there are two clear distinctions, the lowlands and highlands) specifically in the lowlands (Southern and East Scotland, although I have also seen highlands mentioned, in the North), in the 1800s, it being originally worn as an outer garment of woven wool cloth by shepherds. However, this would appear to be referencing the related shepherd’s check design. Although close in nature, there are indeed subtle differences, of which for the sake of exactness should be preserved. That said, likely houndstooth evolved from the shepherd’s check. I now propose to separate the two. Now, as I show in my newspaper researches, houndstooth, as a strict term, was introduced, in the fabric context much later, of 1925 (of an Australian newspaper). Again, pictures are lacking. Whether these accounts are indeed of the now commonly accepted weave are unclear. Confusion also arises to attribution, from supposedly authoritative sources, which are just plain wrong. For instance, the Merriam-Webster dictionary records the term houndstooth was first in use in 1936, which is just risible. Also see the related page ‘definitions’, where for each houndstooth-related term (such as shepherd’s check, dogtooth, Prince of Wales Check, and many others, I show the distinctions.

Variations of Motif Also, to add more fuel to the fire of uncertainty, the pattern has variations in the tessellation. Sometimes it is shown as a strict tessellation, whereas in other instances it has an ‘adjustment’, described as cursive, rather than as individual tiles. Also, the term is applied to other tessellations not strictly pertinent to the ‘standard model’! Indeed, at times any generic black and white tiling with jagged or steps to it is appended with ‘houndstooth’. Loe Feijs succinctly describes this as best regarded as not as single pattern, but rather a family, and of which has much merit. Why Titled Houndstooth or Chicken's Foot? An open question, to me at least, is quite why the pattern is titled as it is, namely houndstooth or chicken's foot, with obvious animal connotations. No one has seemingly looked at this in any detail, with the term used without consideration as to a canine or chicken source. To this end, I now thus examine both: Houndstooth - I have looked at a picture of canine teeth, with the (French) illustration below seemingly ideal for such purposes, with a full dentition of canine teeth, along with the root. Further, it is an open question if there even is an allusion to the tooth root in the title; should this be included or not? No matter, I thus include the possibility. As can be seen, there are a variety of shapes here, simply described as jagged and curved. Which, if any of these, most resemble the standard houndstooth? Strictly, I struggle to identify any here, with or without the inclusion of the root. An (obvious) observation is that some are more jagged than others, which more closely resembles the standard houndstooth pattern. In general, the term more closely resembles the molars. Certainly, the canines and incisors can be ruled out. In particular, that of the precarnassières (premolars) perhaps bear the best resemblance, although the correlation is very far from exact. From the picture, it would thus appear to include the root in the description, rather than the teeth showing above the gum. Overall, therefore, the association is likely with the jagged appearance of the (molar) tooth broadly resembling the jaggedness of the pattern, rather than a strict one-to-one correspondence. However, I am open to debate on this. Dog Dentition Chicken's Foot - Another name given to the design is that of ‘chicken’s foot’ (and variants on the theme), and of which I again struggle to see. However, there is another possibility, not of the foot itself, but of the footmarks made by the chicken. The Australian paper The Mail (Adelaide, SA) of Saturday 12 August 1933 states: There are also blouses of plaid taffeta and of a new material called chicken's foot, in which the pattern somewhat resembles the footmarks made by a chicken in soft soil. At a little distance it looks like a checked fabric. Indeed, one would perhaps think that the titles given (teeth and foot) would bear at least some resemblance, even if heavily stylised to each other, but I do not see this. Has anyone any thoughts on this? Chicken Feet, left, Chicken Footprints, right And there is yet more vagaries! The plant Quackgrass, with the Latin name Cynodon dactylon, with a dog root to it (see below), is known as ‘dog’s tooth grass’, and yet despite the name bears the plant bears no obvious tooth resemblance but more properly appears to resemble a chicken’s foot! Now for the science bit… The genus name Cynodon was derived from the Greek kuon, dog, and odous, a tooth. The specific epithet dactylon is derived from the Greek daktulos, a finger, and refers to the inflorescence which is digitate (arranged like fingers on the hand). Eight species of Cynodon are found in southern Africa. The plot thickens... Nomenclature A veritable minefield! The term ‘houndstooth’ and obvious variants such as ‘houndstooth check’ or ‘hound's tooth’, and synonyms dogstooth’, ‘dogtooth’ or ‘dog's tooth’, is not invariably used; it masquerades under a variety of other names, such as Crows Feet, Goose Feet, Shepherds Check, Four-in-Four Check, Guncheck, Glen Plaid, Vichy, and Pepita, all to greater or lesser degrees. And there is still yet more! The smaller version of this print is referred to as ‘puppy's tooth’. The ‘Four in Four check’ term arose as a result of its creation, with a twill weave created by alternating groups of four black and four white threads together. The old fabric makers created the stair-step appearance by forwarding one thread per column. Further, it is seen not just in the UK and USA, but rather worldwide, albeit to differing degrees. It is titled differently in foreign countries, with notably Pied-de-Poule (France) (which translates as ‘Chicken’s Foot’, Hahnentritt/Hahnentrittmuster (Germany), Hanenvoet and Hondetand (Dutch), Pato/Pata de Gallo (Spain), 千鳥格子 Chidorigōshi (Japan) and Pepitka (Poland). In short, the terms are handled inconsistently, partly synonymous, and sometimes used contradictory! Certainly, ‘houndstooth’ has become the de facto generic description. As a result of such vagaries, imprecision rules. This essay is an attempt, probably futile, to at least bring a modicum of order. Originating in the Scottish Lowlands or Highlands? In my researches, it can be seen that as to origin matters, likely referring to the shepherd’s check rather than houndstooth, there appears to be some doubt as to the exact region; I have seen both the Scottish Lowlands and the Scottish Highlands credited. Therefore, I now examine the rival claims, and try and bring a degree of accuracy to this. Of course, the authorities differ in their substance, of which in matters of veracity I favour print over (most) hobbyist websites. As ever, it’s complicated… are we talking about shepherd's check or houndstooth here? It's anyone's guess... Wikipedia is quite shocking in its slackness, giving: Contemporary houndstooth checks may have originated in woven wool cloth of the Scottish Lowlands This supposedly quotes Dunbar [1]. However, houndstooth is nowhere mentioned in the book! Admittedly, Dunbar, p.151, is referring to the shepherd’s check in the book: The shepherds’ check was ‘the traditional pattern of the shawls or plaids worn by the Border shepherds and introduced into the Highlands...’. Jonny Beardsall, a hat designer from England, referring’ to houndstooth, gives the ‘Scottish lowlands’ and is more exact as to the place, although his quote is not sourced: Houndstooth originated in the wool cloth of the Scottish lowlands and this was woven in Hawick in the Borders. Annoyingly, this is not sourced, and given his background, it is doubtful if this is his own research. Esther Tyreman gives: It was worn by Shepherds to keep them warm on the Scottish Highlands. Annoyingly, this is not sourced, and it is doubtful if this is her own research. And don’t you just know it, there are some vagaries of defining the difference between the Lowlands and the Highlands! A potted account of the differences, from Wikipedia: The Lowlands The Highlands is a historic region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the later Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Scots replaced Scottish Gaelic throughout most of the Lowlands. The term is also used for the area north and west of the Highland Boundary Fault, although the exact boundaries are not clearly defined, particularly to the east. The Great Glen divides the Grampian Mountains to the southeast from the Northwest Highlands. The Scottish Gaelic name of A' Ghàidhealtachd literally means "the place of the Gaels" and traditionally, from a Gaelic-speaking point of view, includes both the Western Isles and the Highlands. And where do you find these sheep? All over the countryside, with the greatest concentration in the Scottish Borders with 17% of the total. (Sorry - another percentage crept in there.) Along with Dumfries and Galloway, the south of Scotland actually has one-third of all of Scotland’s sheep. So what is it then, the Lowlands or the Highlands? Shepherd’s Check or Houndstooth? You pays your money and you take your choice.... The jury is out. To settle the matter definitely, more books and articles will have to be examined, which is pending. References [1] Dunbar, John Telfer. The Costume of Scotland, London: Batsford, 1981, 1984 1989. Web There are so many websites stating that it originated in the Scottish Lowlands and to a lesser degree the Highlands, albeit all invariably never reference their respective assertions! This being so, I thus see little point in an all-exhaustive listing here. The two links here provide typical examples, and serve for a whole host of others: Beardsall, Jonny. http://www.jonnybeardsall.com/?product=swinsty-cap Tyreman, Esther. https://www.yorkshirefabricshop.com/blog/focus-on-pattern-houndstooth/ Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Houndstooth https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scottish_Lowlands https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scottish_Highlands Sheep Distribution. https://must-see-scotland.com/sheep-in-scotland Open-Ended Questions However, despite my extensive researches particular of late 2019-early 2019, which left previous researches far behind, much remains of an open-ended nature. Open questions abound: 1. The holy grail of my research remains: who coined the term ‘houndstooth’ (or of its many variant spellings)? 2. When did it came into being? This is uncertain. The earliest reference (not from the commonly given UK and Scotland) is from an Australian newspaper, of 1925: The Herald (Melbourne, Vic.) Saturday 9 May 1925 p. 16 of a fashion article, by Fonthill Beckford, with: I have also seen some delightful reproductions of Glenurquhart, hound's tooth, and shepherd's checks, but all very small and neat. Taken at face value, thus would thus appear to be the country of origin. However, this would appear to have been a syndicated report, possibly from the UK paper the Daily Mail. Unfortunately, I am unable to check this as this archive is unavailable to me. Can anyone antedate this? 3. The order of terminology. The general impression is that the pattern was referred to initially as houndstooth (from Scotland), from which related and non-related variants then emerged, such as dogtooth, the French term pied de poule and chicken foot, and to a lesser extent puppytooth and pepita. However, my researches show that this is not so. Dogtooth, pied de poule, chicken foot (and even amazingly pepita) all predate houndstooth, some by more than two decades! Yet how can this be so? It doesn’t make sense. Possibly, there is indeed earlier newspaper references to houndstooth, yet if so, I cannot find it. 4. What is the country of origin? Frequently quoted is Scotland, but this is shown not to be so! All the indications are that it began in France, of 1894! The earliest Scotland reference is as late as 1932! Amazingly, there is even a Netherlands reference, 1931, that predates this! 5. When did it make the leap from a (jagged) weave to the print, typically of a simplified nature? 6. How did it spread worldwide? Again, with uncertainty as to origin it is difficult to determine. The earliest reference, of 1894, namely pied de poule, is not from the UK, but rather from France! The general impression, or of a logical assumption, would be from Scotland, to England and then to France. However, there is no evidence for such a dispersion. Further, with the UK links to Australia, it arrived there by such means. As ever, I am open to further information to shed new light on these open questions.

Acknowledgements Yoshiaki Araki, for details of the 16th century Japan tea vessel. Created 17 May 2012. Updated 19 November 2015. Major update 6 November 2018, and ongoing as of 22 February 2019, with a wholesale rewrites and more picture additions from the previous two, all of which leaves the previous writings far behind. |