Alex D. Palmer (9 October 1920–1 April 2013), born Detroit, latterly of Chicago, US, can be described as a major figure in cluster puzzle history (although of course not known by the title of the day), with numerous, high-quality themed instances of a cartoon-like appearance, of a variety of subjects, albeit with varying degrees of the higher principles of tessellation, of no gaps or overlaps. Indeed, it is through Palmer himself that I have chosen the defining title of the genre, it lacking an ‘official’ designation, despite the perhaps not obvious description. Simply put, Palmer can be considered as the person who brought the genre to prominence, in a commercial, jigsaw puzzle sense. Although there are indeed earlier commercial instances (such as by Elspeth Eagle-Clarke and Arthur Nugent), and indeed of substance, Palmer took the venture into greater heights, in association with the Cadaco toy and game company of Chicago in the mid to late 1960s, with sales in the hundreds of thousands. By the relatively high number of puzzles produced (seven), their inherent quality, and the sheer volume of sales, I consider that Palmer should have the honour of the title of their type, hence ‘Cluster Puzzles’.

For once, documenting is a breeze, as the work has effectively been done for me by Kelvin Palmer, the designer’s son, who has self-published a book, The Collector’s Guide to Cluster Puzzles of the 1960s and 1970s, of 2003, 48 pp, giving a detailed history, and is a most pleasant read. I strongly recommend it. This gives a detailed biography as well. Further, albeit very much secondary, but still of importance, is that of the advertising detail from Cadaco. However, somewhat oddly, in jigsaw puzzle circles, the book is very much ignored, and is only quoted occasionally, and certainly not discussed in depth. Be all as it may, the book is a veritable treasure trove, and of which I lean heavily on, as well as a website maintained by him, along with additional thoughts upon enquiries with Kelvin.

However, despite an abundance of advertising and promotional material from Cadaco in the book, and indeed, elsewhere, documenting their role is not straightforward. There are many different releases and formats as documented in the book. Further, the numbering is not always consistent. Indeed, even for the ‘super enthusiast’ such as myself, I lack the will to detail the intricacies beyond a bare-bones approach. Kelvin Palmer

The story began in 1960, with a prototype named Funny-Fits, a one-off, of hand-painted plastic, although this never went into production, albeit parts were later in effect reused. In chronological order, which was then produced commercially with Cadaco, this was followed by seven puzzles: Jumble Fits, 1964; Animal Jumble Fits, 1965; Figments, 1965; Sports, 1966; Make-Up, 1965; Doodles, 1966; Whimsies, 1966, and Unlikely Story No. 1, 1967. These differ in style within two broad various groups. Animal Jumble Fits, Figments, Doodles, Whimsies, and Unlikely Story No. 1, 1967 adhere to the tessellation ideal, albeit with reservation at times, whilst Make-Up and Sports are notably more relaxed, to be generous. Strictly, these are little more than space-filling at times, requiring next to no skill, as I have discussed on the main page. The other puzzles more rigidly adhere to the tessellation principle, albeit with the occasional rounding off and forced definitions. Although there is perhaps, to the purist, more of this than would be considered ideal, this is not to the detriment of the puzzles overall; certainly, there is nothing ‘excessive’ here as seen with others. A recurring aspect, aside from Animals, the first puzzle, is that these feature the adventures of a fictional character, Alec Zandimer Plerp (based on Palmer himself), with his glamorous secretary, Merma. As a rule, save for Animals, for each instance there is a mix of types, whole-bodied, amputations, true-to-life, and fantasies. The puzzles typically have a consistent and high range of numbers of pieces, from 29 to 34, culminating in a 48-piece instance, Unlikely Story No. 1, all a relatively high number. The relative outlier is Unlikely Story No. 1, the last, arguably his masterpiece. Such a relatively large number each time, given the quality aspects involved, is most pleasing.

Seven puzzles were produced, of largely themed instances, with a relatively large number of pieces, and furthermore all of an ideal upright orientation. The puzzles differ in their degree of interlocking. Animals, Figments, Doodles, Whimsies, Unlikely story No. 1 are of an ideal, close interlocking nature. On occasions, minimal ‘wriggle room’ with these is introduced, for a better portrayal, but this is largely of a minimal nature. Indeed, the preliminary pencil sketches of Figments, Doodles and Whimsies show no ‘wriggle room’ whatsoever. Simply stated, the finished works show a general ‘rounding off’ on occasions in places. Certainly, I myself, of which I regard this issue of fundamental importance, have no qualms about this usage here. Certainly, there is nothing ‘excessive’ here (as much beloved by other so-called deluded ‘tessellation’ artists that permeate their work, with wide, open spaces that destroy the principle of tessellation). However, Sports and to an extent Make-Up do indeed have a considerable degree of ‘wriggle room’, and so are consequently marked down in comparison.

A pleasing feature of all seven of the puzzles is that they are all based on a theme (although on occasions the term is used a little loosely here), of which as detailed on the main page, is an ideal attribute. Further, they all largely appear in an upright orientation, rather than ‘anything goes’. Again, this adds to the difficulty but also gives a better cohesiveness, all things being equal with quality issues. These can be differentiated in two main ways. Truly themed are Animals, Sports, Whimsies, Unlikely Story No. 1. Of a vaguer premise in this regard are Figments, Make-Up, and Doodles. Nonetheless, these remain of inherent quality per se; it’s just that I have concerns over the titling and content thereof, which is of secondary importance to the quality aspects of the puzzles themselves.

Curiously, the rendering of them echoes the differentiation above; Animals, Figments, Doodles, Whimsies, and Unlikely Story No. 1 are of a fun, cartoon-like appearance, whilst Sports and to a certain extent Make-Up are more ‘serious’ and with proportionate figures. Generally, Palmer favoured a cartoon-like portrayal, with a multiple colouring (with a black surrounding outline), of which perhaps due to the demands of the cluster premise is arguably ideal, in that such a presentation seems to fit in well with the motifs, which typically adopt a series of unusual poses, perhaps best displayed in a cartoon-like manner. An open question is to the differences.

Of interest is to which of the puzzles proved a commercial success, or otherwise. Cadaco (p. 14), in correspondence with Palmer, stated ‘...Animals and Figments titles constitute by far the major portion of our Cluster Puzzle sales’. Animals are a popular theme as sellers in whatever medium, and so such a themed puzzle success here is thus understandable. Perhaps Figments, due to its whimsical nature, also appealed to the imagination. However, I fail to see why these two, in particular, stood out by far; other puzzles are of equal styles, such as Whimsies, and to my thoughts, of likely equal success. That said, perhaps this is more nuanced, I have not seen any sales figure documents.

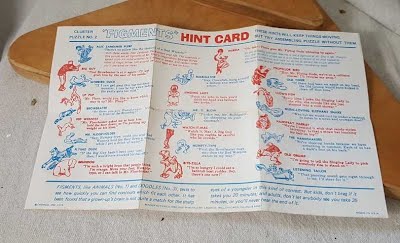

To aid the solver, included with the puzzles was a ‘Hint Card’, with a series of humorous text clues, with, depending on the puzzles, zany character names, which for the frustrated assembler gave clues as to the assembly. This is I believe the only such guide in the genre. The reason for its inclusion is that assembling the puzzle is not quite the same as doing a normal jigsaw, in that no clue is provided with different coloured individual pieces and so is thus harder to complete. Indeed, so difficult that such assistance can arguably be considered essential.

The book is a veritable treasure trove of information and detail. There is nothing else quite like it. However, even so, there were still some queries that perhaps only the super enthusiast such as myself would be interested in. For instance, no mention in the book is made of Escher possibly acting as the inspiration. Also of interest is the Alec Zandimer Plerp character, and other matters. In this regard, I contacted Kelvin with a series of email questions of 2013. His replies were most illuminating. Below I have assembled the more interesting comments that contain details that are not in the book.

26 October 2013 Regarding Escher, my father was certainly a fan of Escher's work although I can't point to any inspiration for Dad's puzzles having come from Escher. Escher's "geometry" was probably what interested my father the most. I remember that Dad made a pretty good 3D model of one of Escher's "impossible" shapes (blivet, devil's fork) out of folded paper. I became an Escher fan in the late 1960s, early 1970s when many of his works became available as black-light posters. My father simply described the revelation that he could "see" and create a cartoon character within any randomly shaped outline. Dad certainly believed that he had conceived the unique idea of "a puzzle with every piece a picture" and applied for a US patent in 1963. In 1967, the patent grant was denied, citing "prior art" from Switzerland in 1946 and from Britain in 1934.

8 November 2013 My father conceived and used both the terms Cluster Puzzle and Jumble-Fits before Cadaco became Involved. record was likely what he would have considered his most ambitious puzzle achievement. Much later, only 10 years ago, I tried to get him to create some new puzzle pieces that would be "joining pieces" to merge the original puzzles into one big one. The new pieces would have fit against the edges of the originals and joined the six smaller puzzles into one continuous grouping. Already in his eighties, this was too taxing for him. He sketched one piece. Those preliminary pencil sketches ARE the process. That's all there was. Once the sketch was done, he set about painting the final art in watercolors. I have the original painted art for four of the seven puzzles. The other three are missing.

14 November 2013 My father had clipped an ad for this puzzle [Escher’s Plane Filling?] in 1968.

19 November 2013 “Tek” was just short for “Technical”. Tek Method Company was not created for the puzzle products. It was already producing draftsman’s drawing templates. Dad had a patent on ellipse guide templates and also produced arrow-head drawing templates. Production of these was small and, again, a very home-spun affair. I have no memory of ever being told “why” his puzzle character was called “Alec Zandimer Plerp”. Just a funny, imaginative, cartoon name. No question though...AZ Plerp WAS my father’s alter ego character. Plerp lived on many years later in a self-published cartoon story book of pen and ink drawings. The story dealt with my father’s obsession about the idea that human genetics were inescapably flawed and that, some day, may be, could be, corrected. Mr. Plerp, in the story, provided the cure.

December 2013 I really don't know how much my Dad did or did not know, or paid attention to, about Escher. I can't suggest that he had or had not seen Escher's Plane Filling works prior to the Cluster Puzzle ideas. My father was a student at Chicago's Art Institute in the late 1940s following WWII. In other words, he studied art. Personally, I would guess that means Escher would not have been unknown to my father, but that is purely conjecture on my part. Certainly, much later, he was showing me books of Escher work.

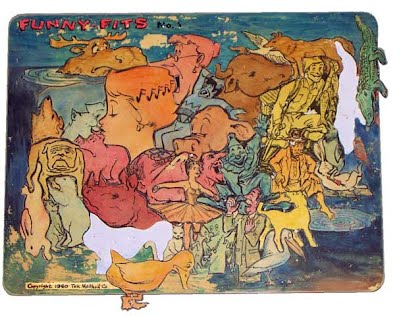

Each artwork/puzzle in detail 1. Funny-Fits, 1960 Kelvin Palmer Being a prototype, the artwork here is not unexpectedly a little different to the later style. In general, this lacks a common theme, a varied assembly of (upright) animals and people, with both whole figures and amputations. An obvious observation is that the motifs are not so easily discerned, with like regions of more or less the same colour. Also, these lack the degree of interior detail shown afterwards. Further, this can be seen to be a strict tessellation, without the rounding of or of gaps, to great or lesser degrees, of later works. Further, some regions are used again in later works. The bulldog, rabbit, standing bear, pig, duck and rhinoceros head can also be seen in Jumble Fits. Also, the wolf, bird, dog, cow head and alligator. The same reclining rabbit with carrot appears in Jumble Fits, but with different surrounding animals. Missing is the Alec Zandimer Plerp character and his secretary, Merma. That said, the scene is indeed set for the later works.

2. Animal Jumble Fits 1965, 34 pieces. Production estimate 12,000 units In general, excluding Sports and Make-Up, this work sets the scene for the following puzzles. A decided theme, of animals (no human figures), is evident, with both whole figures and amputations. More attention is paid to the interior detail, as well as colouring, of which each animal is now more easily discerned. As alluded to above, two of the regions of Funny-Fits are reused. The principle of tessellation is loosened a little here but is still the guiding principle. For instance, the giraffe has faux articulations.

3. Animal Jumble-Fits 1965, 34 pieces. Production estimate 8,000 units (or 100,000, p. 25) This is the same artwork as above, with the only difference being that instead of a white border a black one is shown. Arguably, as this is essentially the same, this could be combined or even excluded from this listing, but as it is in the book as a dist work I have decided to include. This is the first puzzle that I term as ‘classic’, of a variety of animals and people, along with a few fantastical creatures, all of a decidedly whimsical nature, mostly whole-bodied, with occasional amputation, with a black border, of which the broad, general format is then adopted, as evinced by Figments, Doodles, Whimsies and Unlikely Story No. 1.

4. Figments, 1965, 24 Pieces. Production estimate 8,000 units (or 100,000, p. 25) Figments are used as in ‘figments of my imagination’. A variety of animals and people appear, along with a few fantastical creatures for the first time, of zany characters, such as ‘Red Weetoz’, ‘Bulbigator’, and others, all of a decidedly whimsical nature, mostly whole-bodied, with one amputation. A black border is given. The principle of tessellation is to the fore, with only minimal forced articulations. The Alec Zandimer Plerp character and his secretary, Merma appear for the first time, albeit separately, and in the following puzzles.

4. Sports, 1966, 30 pieces. Production estimate 50,000, p. 25 Sports is noticeably different in style to the preceding works, with the principle of tessellation considerably reduced to the point of the sporting figures being no more than mere space-filling. The figures are all broadly true-to-life, and lack the previous whimsy. Plerp appears but not his secretary. Kelvin relates the background here as to the theme on p. 10 of the book. In short, Alex had no interest in sports, and so likely it was a Cadaco idea. The following puzzle, Make-Up, is also similar in style, albeit with a slightly more tessellation principle, but is still considerably loosened.

5. Make-Up, 1966, 28 pieces. Production estimate 50,000, p. 25 Make-Up follows in the style of Sports, with the principle of tessellation considerably reduced, to the point of mere space filling, albeit perhaps a little more adhering, but even so, there is still much mere space-filling here. The motifs, of both whole figures and amputations at times bear little connection to Make-Up. The figures, set against a red background, are all broadly true to life, with occasional whimsy. It is not early clear if Plerp and Merma both appear. What appears to be them together at first sight is captioned ‘Starlet Being Made Up’. Kelvin relates the background here as to the theme on pp. 10-11 of the book, with horror movies to the fore.

6. Doodles, 1966, 31 pieces. Production estimate 30,000, p. 25 Doodles returns to the type of tessellation principles, as evinced by the more classic style. A variety of animals and people appear, all of a decidedly whimsical nature, along with a few fantastical creatures, mostly whole-bodied, with five amputations. An interesting feature is that the head of the boy, top centre, appears to be of an anamorphic projection; view from the side at a raking angle. A black border is given. An innovation here, and also to be seen on the following Whimsies, is that of having the border pieces truly interlocking, to give the assembled puzzle greater integrity. Previously, the pieces were overwhelmingly push-fit, and so easily dislodged. This detail is given on the preparatory pencil sketches on p. 46 and is also told by Kelvin on p. *. Plerp appears, doodling, hence the title, with Merma.

7. Whimsies, 1966, 29 pieces. Production estimate 30,000, p. 25 Whimsies continue the tessellation principles, as evinced by the more classic style. A variety of animals and people appear, all of a decidedly whimsical nature, along with a few fantastical creatures, mostly whole-bodied, with two amputations. A black border is given. Plerp appears adjacent with Merma.

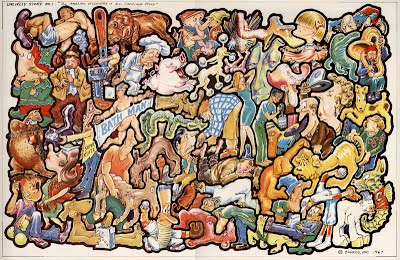

8. Unlikely Story No. 1 1967, 48 Pieces. Production estimate 1,000 units (or 20,000, p. 25) Unlikely Story No. 1, the final work, continues the tessellation principles, as evinced by the more classic style. The title implies more, and indeed is stated as such on the hint card, but this did not materialise. The hint card also gives an explanation of the premise, with Plerp’s experiment on mixing Nitroglycerin and artist ink. Pending the addition, Merma put her fingers in her ears in case of an explosion. Arguably, this can be considered as his masterpiece, with the increase in the number of figures to 48, (previously 24-34), commensurate with quality. A variety of animals and people appear, all of a decidedly whimsical nature, along with a few fantastical creatures, mostly whole-bodied, with three amputations. Plerp appears adjacent with Merma. Kelvin also relates the background here as to the theme on pp. 12-13 of the book.

Table of the Puzzles Of interest is an analysis of the more ‘vital aspects’ of the puzzles, in terms of the titles, number of pieces, the date, tessellation principle, border/background colour, Plerp and Merma, and amputations, and see what can be extracted. To this end, I have thus compiled a table of these aspects.

And finally, what of the man himself? Again, aside from the book, little is known. Below I repeat his obituary (the one and only?) on Kelvin’s page: Alex D. Palmer It is with great sadness that we share the passing of Alex D. Palmer, 92, on April 1, 2013. He was born in Detroit on October 9, 1920 to the late John and Catherine Palmer. He served in the Army Air Corps in WWII as a nose gunner on a B-24 until he was shot down and survived being a POW. He married his wife, Marian, over 66 years ago after returning from the war and moved to Chicago to start their life together. A graduate of the Art Institute of Chicago, he was a man of many talents able to blend his love of art and science. He was an inventor, illustrator, cartoonist, author, poet, puzzle designer, humorist and original thinker. Preceded in death by his parents; sister, Donna Malin; wife and soul mate, Marian, he is survived by his brother Daniel (Florence) Palmer; sister, Ellen Boyd; daughter, Janet (Tom) Lukes; son, Kelvin (Vicki) Palmer; grandson, Kyle (Tamara) Lukes; granddaughter, Christina Palmer and many nieces, nephews and cousins. Per his wishes, cremation has taken place, and a private family celebration of his life is planned where many memories, tears and laughter will be shared. He was a self-effacing man with a wry sense of humor who chose April Fool's Day as his final commentary. In his honor, enjoy a beautiful work of art, repeat a great joke or share a poem with a loved one. We will miss him always. Summary As a broad, general sweeping statement, I like these very much, albeit with qualification, of Sports and Make-Up and reservation, and with the tessellation principle in general across all the works. Indeed, Sports and Make-Up just don't really do it for me, in two ways, although the figures are true-to-life, they lack the ‘vitality’ of the other cartoon-like instances, as well as being nothing more than space-fillings. Further, there are also issues with the tessellation principle, with at times forced definitiontions. However, this is only a relatively minor quibble, the strict principle is generally observed, and indeed, in the preparatory drawing, these are indeed of a true tessellation. It would appear that for the sake of a better presentation Palmer simply ‘rounded off’ in places, rather than inherent forced definitions. A personal favourite is Unlikely Story No. 1, in that although there are other puzzles in the same style, such as Figments, this is ‘better’ in that it has more pieces, with the same quality aspect being commensurate. Throughout here, the premise is of a ‘fun’ puzzle, and there's nothing wrong with that. To directly compare these with others, of more adherence to real animals and people would be unfair, as the respective designers are simply presenting differently. It doesn't matter about the style, whether high brow, or low brow and everything in between. The question is, is this good art? It is.

Timeline 1920 Born Detroit, 9 October 1960 Funny-Fits, a prototype 1964 Jumble Fits artwork 1964 ‘Tek Method Company’, of Chicago, established (family concern) 1965 Patent apple for but turned down (prior art) 1965 First press coverage in The Tipton Daily Tribune, Tuesday, July 13, 1965, and syndicated 1965 Animal Jumble Fits and Figments artwork 1965 Contract signed with Cadaco in October 1966 Cadaco begins marketing 1966 Sports, Make-Up, Doodles, and Whimsies artwork 1967 Cadaco ad featuring Doodles and Whimsies in Toys and Novelties trade magazine, January 1 1967 Unlikely Story No. 1 artwork 1968 Overall sales for the year 75,000 1968 Pitches further ideas to Cadaco with titles of ‘Quirks’ and ‘Fancies’, but unrealised; no artwork is undertaken 1968 Unlikely Story No. 1 as a record 1977 Cadaco release a three-puzzle set 1988 Cadaco cease carrying the titles 2003 The Collector’s Guide to Cluster Puzzles of the 1960s and 1970s by Kelvin published. 2013 Dies Chicago, 1 April

Acknowledgements Kelvin Palmer, for much additional information on his father’s work.

References What is surprising, given the 1960s popularity, is how little the puzzles feature in books, articles, newspapers, and latterly the web. For each category, there is essentially next to nothing! Have people already forgotten about them? I am most surprised.

Books What is surprising is how little the puzzles feature in books aside from Palmer; indeed, there is effectively nothing else! Surely someone must have written about them? Palmer, Kelvin. The Collector’s Guide to Cluster Puzzles of the 1960s and 1970s. Self Published, 2003 Williams, Anne D. The Jigsaw Puzzle. Piecing Together a History. Berkley Books, New York, 2004 A mention to the Palmer book in passing, in Appendix B, p. 202. Not discussed in the main text.

Web http://www.azplerp.com/ Kelvin Palmer website, with much detail on the puzzles https://www.joelacey.com/blog/great-illustrators-of-the-past-alex-palmer Fan of the puzzle. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JetPk7fhQJw 21.52 video of a fan assembling the Jumble Fits and Figments puzzle. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SPOz_QjIBtM 2.51 video http://www.robspuzzlepage.com/jigsaws.htm (Where I first became aware of Palmer’s work (and the genre), in, I believe 2013)

Articles Again, what is surprising is how little the puzzles feature in articles; indeed, there is effectively next to nothing! Surely someone aside from Kelvin must have written about them? Palmer, Kelvin. ‘By The Numbers - eBay Puzzle sales’. Game & Puzzle Collectors Quarterly June 2003 (Summer) Vol. 4, No. 2, p. 12. Palmer, Kelvin. ‘Jumble-Fits, Cluster Puzzles, A.Z. Plerp’. Game & Puzzle Collectors Quarterly September 2003 (Fall) Vol. 4, No. 3, p. 9. An introduction by Kelvin, upon his renewed interest in 2003 , with a brief history, a request for contact with enthusiasts of the puzzle, and announcing of the book and website. ? Game & Puzzle Collectors Quarterly, June 2004 (Summer) Vol. 5, No. 2 (inconsequential)

Newspapers What is surprising is how little the puzzles feature in newspaper archives; indeed, there is next to nothing of any substance! And even when there is something, not all are distinct references, as some are syndicated, as are all of the 1965 references. Further, some are not even a dedicated entry, being part of a general discussion, such as on antiques! The most in-depth discussion, independently, is by Richard Moon and John Filatreau whilst the only illustration is by Filatreau. ‘Cluster Puzzles Latest Twist’. Daily Independent Journal, Tuesday, July 6, 1965 ‘What’s New’. The Tipton Daily Tribune, Tuesday, July 13, 1965 ‘New Puzzle’. The Grenville News, Greenville South Carolina. Friday, July 16, 1965 ‘Puzzle Fun’. The Pantagraph. Thursday, August 19, 1965 ‘Games’, by Richard Moon. The Times - Weekend Saturday, September 28, 1968, page 11A ‘Cluster Provide challenges some youths meet better than adults’, by John Filatreau. The Courier-Journal, Sunday, September 9, 1979, H 17 ‘Antiques and Collecting’ Florida Today, Saturday, February 26, 2005 ‘Specialty Tables hold Real Appeal’. (final edition), by Ralph and Terry Kovel. Orlando Sentinel; 27 February 2005: J14. ‘Tables of content’, by Ralph and Terry Kovel. The Record, Thursday, March 3, 2005 The Journal News

As ever, can anyone add to the story?

Page History Effectively, this is a new, dedicated in-depth entry, of 20 May 2020. However, I have part-used some previous writings on the Palmer entry on the main generic page. That said, that text was lightweight in comparison to this here, albeit still in relative depth in comparison with others on that (long) page. Quite when this was written is unclear; I neglected to add this detail to the page history listing at the foot of the page. However, it was at least 28 May 2014, of which I have a print-out of that date (and of 2017). Save for picture additions, the text has remained the same, as of 2020, of which in line with other entries that have been rewritten, I now simplify the old entry, having taken the precaution of saving the old entry.

Page Created 20 May 2020 |

Cluster Puzzles >