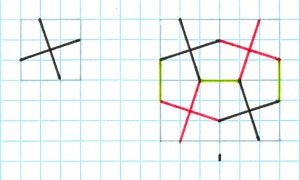

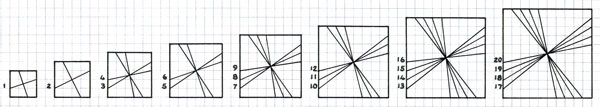

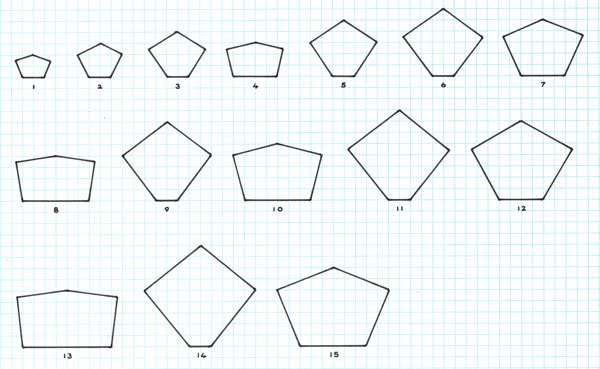

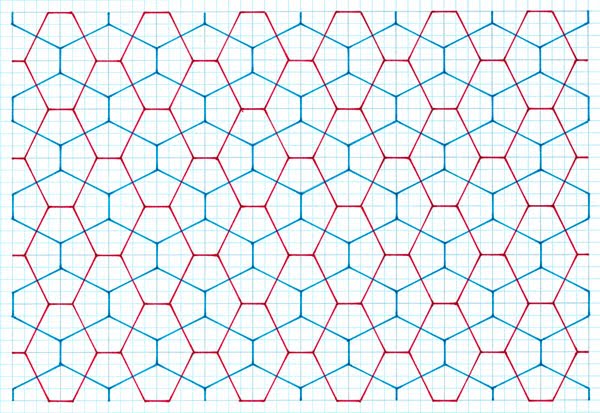

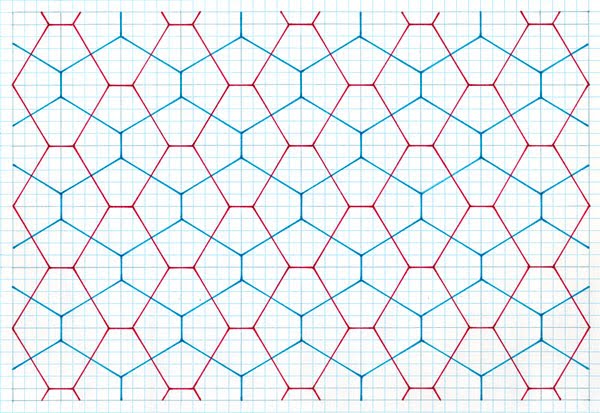

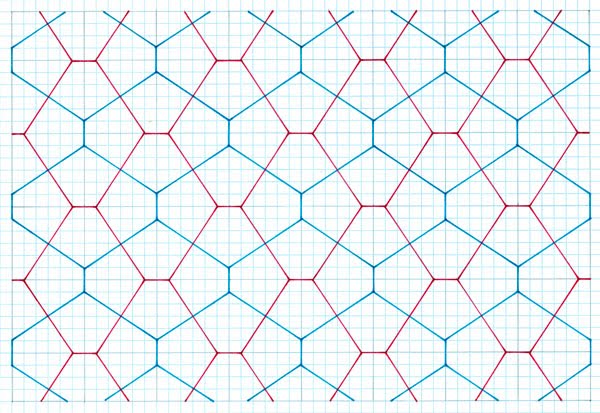

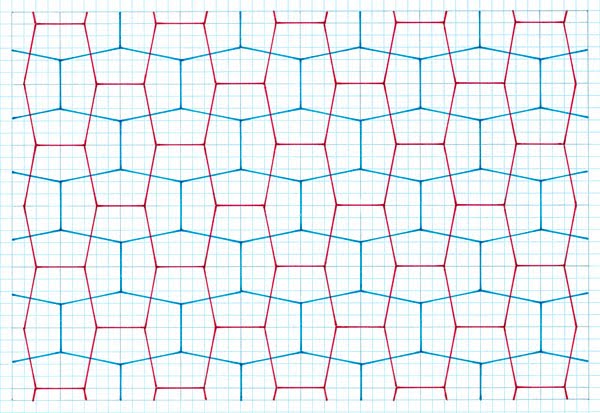

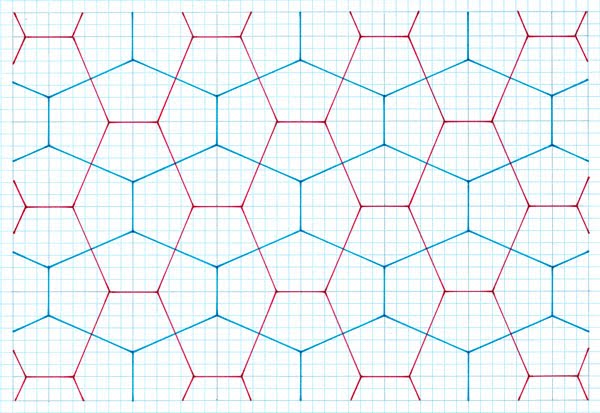

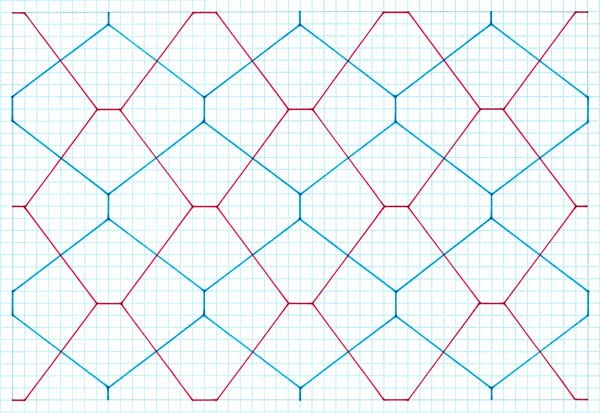

Stick Cross Method The particular study consists of arguably the most simplest possible constructions for a Cairo-like tiling, namely that of a stick cross, of two equal arms, possessing order 4 rotational symmetry, placed in a square matrix, and then successively reflected. The study is presented in a series of three stages: 1 shows the premise, 2 shows the tiles arising from this as tilings, 3 gives comment on the findings, effectively as a summary. Premise  Figure 1: Reflected Stick cross principle The premise of this particular construction is one of undoubted simplicity, of symmetrical stick crosses reflected in a square matrix, as according to unit size intersections; the example above based on a 3 x 3 unit, Figure 1. Two different coloured lines that show the ‘reflected placement’ premise.As can be seen this, this basic procedure can be varied and so make for considerable differences of the cross, in terms of its ‘angularity’, and scale. The cross can vary in its ‘angularity of placement’ as according to the underlying intersections of the unit square utilised and by increasing the unit size of the square, Figure 2.  Figure 2: All Possibilities of Stick Crosses Figure 2 shows a sequence, beginning with the smallest unit size possible, 3 x 3, continuing to 10 x 10. Of course, one could continue, this being an infinite sequence, but for the sake of practicality I restrict the analysis to the ‘first few’ up to 10 x 10, giving a Set of 20 tiles. As will be realised upon a moments reflection, where the unit size doubles then a repeat tiling is formed, of which these can be omitted. For the record the repeat examples are: 1, 6, 15; 2, 11; 3, 18; 4, 20. Excluding the repeat members thus gives a Set of 15 tiles, Figure 3. Figure 3: A Set of 15 Distinct Tiles As can be seen the proportions of the resulting pentagons can be seen to differ markedly, from a ‘near’ rectangle (13) and ‘near’ square (11), of which rectangles and squares is indeed obtained if the stick cross is placed at the minimum and maximum points. Nonetheless, despite such extremes, all the while the tiles still retain their ‘Cairo-type’ tiling properties as previously detailed.Tilings Having thus determined distinct individual tiles, these are thus shown as tilings, Figure 4. Note that for the sake of a more concise presentation, I show only the first five examples of the sequence, followed by some examples that are of ‘of special interest’.  No.1. Angles of 108°.43’, 143.13; side ratio of 2: 1.58  No.2 Angles

of 116° 57’,

126° 8’;

side ratio of 2: 2.24  No.3. Angles of 120°

6’, 118° 07’; side ratio

of 2: 2.92  No.4. Angles of 101° 31’, 157° 38’; side ratio of 4: 2.55  No.5. Angles of 123° 69’, 112.62; side ratio of 2: 3.61  No. 7. Angles of 113°

2’, 133° 6’; side ratio

of 4: 3.81  No.9. Angles of 126° 87’, 106° 26’; side ratio of 2: 5 Comments As can be seen, when shown as a

tiling this particular premise always results in a single pentagon, and so being a minimum number is obviously

‘aesthetic’ (as I later show with other, different premises, is not always so. Obviously,

2, 3, 4 or more pentagons in a composition lack this (of which I show in

succeeding studies), as interesting as they (or can be) are. The subsidiary

hexagons are at right angles, which again is aesthetically pleasing, and as

above, this is not necessarily so with others. Of interest is to compare the pentagons so discerned with those of the ‘aesthetic’ type frequently cited (although without in situ evidence), namely the equilateral and dual types, and see how close these can come to such ‘aesthetic’ examples, and indeed of the in-situ pentagons themselves: Equilateral 114° 18’ (2) and 131° 24’ Tiling 7/15, with angles of 113° 2’ (2), and 133° 6’ is close. Side ratio 4: 3.81 32.4.3.4 120° (3) 3/15 is very close, with almost alike angles (120°.96’, 118°.07’). In situ pentagons 108° 26’ (2), and 143° 8’ (as given by Macmillan) Tiling 1/15 is closest, remarkably so, with angles of 108° 43’ (2), and 143° 13’ (as given by Bailey). Side ratio 2: 1.58 A simple observation is that these are collinear to the ‘nearest neighbour’, which thus has implications on this. Of note is that the only square-based example with the same condition is 1/15. Furthermore, it can be seen that the angles are an extremely close match, differing at most by a trifle over a half degree. This begs the question as to whether it is possible to discern the difference as an abstract argument. I very much doubt it, given the fine margins involved, even for a theoretically ideal tile, never mind an in situ example. |